An Ancient and Interesting Tradition that has been Left to Die[0]

By Gianni Materazzo

The statue on display at the Church in Torricella, in a naïve, rough

style, is typical of a certain religious iconography. One is struck by its

small proportions, the vaguely childlike features of the face, and this

suggests that it might be that of a child or an infant. One is also struck

by the high-sounding, even bellicose name: Marziale (Martial). This name derives

from the Latin, Mars[1] (Marte) God of War, which was quite

commonly used in ancient Rome. To me personally it evokes the sweet

atmosphere of the village, with its moods, its people, and the many

Torricellans who adorn themselves with this name and its diminutives:

Marziale, Marzialuccio, Marzialino.

The statue on display at the Church in Torricella, in a naïve, rough

style, is typical of a certain religious iconography. One is struck by its

small proportions, the vaguely childlike features of the face, and this

suggests that it might be that of a child or an infant. One is also struck

by the high-sounding, even bellicose name: Marziale (Martial). This name derives

from the Latin, Mars[1] (Marte) God of War, which was quite

commonly used in ancient Rome. To me personally it evokes the sweet

atmosphere of the village, with its moods, its people, and the many

Torricellans who adorn themselves with this name and its diminutives:

Marziale, Marzialuccio, Marzialino.

If you ask around, however, the doubts and the questions soon emerge. The Patron Saint of Torricella was a child: he was just seven years old and he lived in the times of Marcus Aurelius[2]

Was the Patron Saint really a child of seven? Is that possible? What could have made a tot of that age be of such importance, meriting that he become a Saint and even a martyr[3]? Many generations of Torricellans have asked themselves such questions, not hiding their perplexity and reserve, so much so that they have often said, "Our Patron Saint is "scompicciato" ("messed up"), in other words, "he wets himself": a frank, knowledgeable expression, alluding to the Saint’s young age.

Yet Marziale, youngest of seven children, despite his young age, together with his mother Felicità[4] and all his brothers (Gennaro, Filippo, Felice, Silvano, Alessandro and Vitale[5]), faced a trial at which they were accused of being Christians. Before judgement and conviction, (the accusers) repeatedly tried first with promises, blackmail and threats and then with torture and beatings/whippings, to induce them to renounce the religion in which they believed. According to the authorities, this religion undermined the order of the state and upset the entire hierarchy of the values upon which the ideologies of the time were based.

Imagine this scene: a Roman mother, (Felicità, a noblewoman, it seems[6], belonging to the "gens Claudia[7]" the Claudian family) stands before the magistrates, surrounded by her seven sons, all of them very young. If you want to let your imagination run wild, think about this taking place in the small theatre at Juvanum. The shouting restless crowd is crammed, packed onto the steps. Some magistrates[8], armed with cuirass[9], helmets and spears, with a fierce and steely air, surround and watch over the accused. Instead the Prefect[10], who presides over the trial, is seated at the centre of the semicircle, on a high stool, swamped by a rich purple toga; in front of him is enthroned the marble image of Marcus Aurelius; a flame in a tripod burns at the base of the statue.

"The Emperor’s statue," the Prefect insinuates blandly, "has been put here before us with a sacred flame burning at its feet. It will suffice if you put a grain of incense into the tripod, to show that you repudiate Christianity." You don’t even need to speak. Then you can happily return home from here….."

Surrounded by her seven sons, and holding the two youngest, Vitale and Marziale, tightly to her, Felicità smiles sadly, and looks at the Prefect with commiseration. Then she turns her eyes towards heaven and stands still, silent, as if in prayer, not deigning to reply to her inquisitor.

"If you insist in being silent," the Prefect hisses at her, barely holding back his irritation and impatience, "I shall be forced to have you tortured: you first and then, if you do not abjure your insensate creed, your children too …… including that little boy you are clutching as if to protect him."

Felicità feels a pang of anguish run through her. The thought that her

sons might be put to such atrocious tortures as are used in these cases torments her and

upsets her terribly. Yet she is unable to deny her faith. Raising her arm to

indicate heaven, anticipating the magistrate’s sentence, she pronounces what

will be a death sentence for herself and for her children, as she shouts,

"My sons, I tell you to look to heaven! Turn your eyes upwards and keep them

fixed there, where Jesus Christ is awaiting you together with his Angels and

his Saints!"

to such atrocious tortures as are used in these cases torments her and

upsets her terribly. Yet she is unable to deny her faith. Raising her arm to

indicate heaven, anticipating the magistrate’s sentence, she pronounces what

will be a death sentence for herself and for her children, as she shouts,

"My sons, I tell you to look to heaven! Turn your eyes upwards and keep them

fixed there, where Jesus Christ is awaiting you together with his Angels and

his Saints!"

Faced with this matron’s unshakeable attitude, the Prefect leaps to his feet and screams at the executioners to scourge[11] her, there, immediately. Felicità is chained to a stone column and is whipped until, prostrate and bleeding, she collapses unconscious. Then, always on the orders of the ruthless inquisitor, she is dragged away and is thrown into prison. Her sons watch this cruel punishment in utter dismay.

The same torture is inflicted on each of them in turn. But each time, before the soldier cracks the first blow of the whip on those slender backs, the Prefect asks each one of them to repudiate the religion to which they have converted. Each time the seven boys, from the eldest, Gennaro, to the youngest, Marziale, strengthened in their stoicism by their mother’s example, reply that they will not ever deny their faith in Jesus Christ.

The last one is Marziale, the Patron Saint of Torricella.

It seems impossible that such a young child could give so penetrating and conceptually elaborate a reply, and yet it seems that this was how he replied to the Prefect, who tried with entreaties and threats to convince at least this one to abjure.

The boy said, "Maybe you, oh ignorant judge, do not know the joy, the eternal beatitude that God sets aside for those who suffer here on earth and die for him. If you did know, you would punish us by leaving us alive. But since it is impossible for you even to imagine it, what are you waiting for to put us to death, me, my mother and my brothers? We do not wish for anything else….."

A procession, by means of which the martyrdom of Santa Felicità and her seven sons is remembered, took place in Torricella right up until about 10 years ago (i.e. until 1986). In the past, as far as I know, there was an elaborate ceremony, regularly, every year, (although lately it was held much less frequently), and somehow it became linked to the rural rites of threshing. Thus we used to see an open procession of a crowd of girls who would parade up and down the "Corso"[12] dressed in regional costume, carrying typical "conche"[13] (water containers) filled with grain (wheat) on their heads. The procession ended with several donkeys, with chests or sacks tied to their large, crude, wooden saddles, which also were piled high with grain (wheat). This wheat had a votive meaning, in as much as in its large quantity it was an offering made to the Church by the people, a really true charitable offering. In fact, when the procession ended, the wheat was left in the sacristy (of the Church).

I have taken part in a couple of these processions. I remember Santa Felicità in a rather confused way as she processed in front of her sons, dressed in a realistic Roman "peplo"[14]. The seven sons followed her in height order (Marziale obviously came last). They too were wearing sandals and tunics appropriate to that era. Then the whole picture was made even more satisfying from the historical point of view, by the presence of a couple of Praetorians (magistrates) escorting the condemned, they too were showing off Roman style clothes, plus armour and helmets, shining with metallic reflections, even though made of horrible papier-mâché. It was a pity that the whole thing was restricted to a march along the streets of the village. It would have been better if the commemoration had been enriched and completed with a representation (re-enactment) of the trial to which Felicità and her sons were subjected. Everywhere in Italy there has been a tendency to restore ancient rites, sagas and ceremonies, which, over the years, had fallen into disuse, guiltily left to be buried in oblivion by lack of love for local traditions and culture. Only recently has there been a change of attitude, with a reawakening of conscience. People have begun to become aware that by ignoring the past we risk losing definitively a precious heritage, losing even the last vestiges of our past, of the history of our country and of ourselves.

It would not be a bad thing if we were to try, naturally with everyone’s consent and contribution, to begin with our own parish, by restoring this very old ceremony which I imagine is deeply rooted in the culture and religious feelings of Torricellans. We could make it more evocative, filled with folklore and interesting teachings, by reconstructing dramatic scenes of the trial of Felicità and her sons according to the popular rite of a holy performance, by means of which many religious festivals were and are celebrated.

Translator’s Notes:

[0] In September 2004, we translated an article by Antonio Piccoli about the recent (2004) feast days and religious processions at Torricella, in which the parts of Felicità and her sons have been added back into the procession – for further details please see:- August 2004 Feast Days at Torricella

[1]

Mars, the Roman God of War - was one of the most worshipped and revered gods throughout ancient Rome. He was the son of Jupiter and Juno and according to legend, fathered Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome, with the vestal virgin Rhea Silvia. Because of this mythological lineage, the Roman people felt as though they were also the children of Mars and he was regarded as their protector. Mars held a special place in the Roman Pantheon not only for his patronly influence, but because military achievement was of such great importance in the republic and the Roman Empire, conquering Northern Africa and much of Europe and the Middle East.The month March (Martius) is named after him. As the god of war, many of festivals were held in the spring, the beginning of the campaign season. He was a god of spring, growth in nature, and fertility, and the protector of cattle. On March 1, the Feriae Marti was celebrated. The Armilustrium was held on October 19, the end of the campaigning season, when the weapons of the soldiers were ritually purified and stored for winter.

Initially Mars was the Roman god of fertility and vegetation, and protector of cattle, but later he became associated with battle. As the god of spring, when his major festivals were held, he presided over agriculture in general. In his warlike aspect, Mars was offered sacrifices before combat and was said to appear on the battlefield accompanied by Bellona, a warrior goddess variously identified as his wife, sister or daughter.

It is believed that Mars was originally an ancient chthonic god of spring, nature, fertility and cattle. He fused with the Greek Ares and became a god of death and war as well.

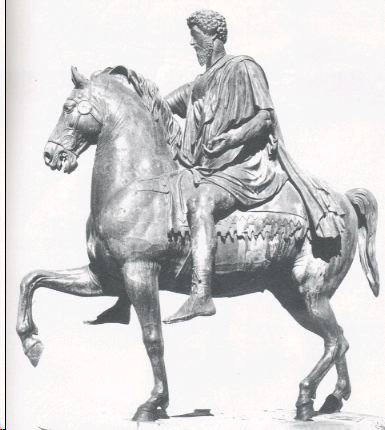

[2]

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus - one of the greatest rulers in Roman history, he was one of the five "good" Emperors; he ruled from 161 to 180 AD. A highly intelligent man, he was one of the foremost intellectual rulers of Western Civilization and a great military leader, yet he desired peace and this is

evident in his philosophical writings.

He was uniquely the only emperor whose

life was moulded by, and devoted to, philosophy.

Civilization and a great military leader, yet he desired peace and this is

evident in his philosophical writings.

He was uniquely the only emperor whose

life was moulded by, and devoted to, philosophy.

Marcus Aurelius was born in Rome on April 26, 121 A.D. into a wealthy, politically prominent family. The Emperor Hadrian noticed him when he was a young child and gave him special educational privileges. Marcus was enrolled in the Equestrians at the age of six and the next year he was given special permission to attend the priestly college of the Salii in Rome, where he was taught by the greatest thinkers of the day, from a variety of cultures.

Marcus Aurelius continued to receive help from Emperors, and he gained in political power. He was adopted by Antonius Pius, the chosen successor of the throne. Marcus married Pius’s daughter, Annia Galaria Faustina, which further strengthened his position both politically and as Pius’s successor. Marcus played a major role in government under his father-in-law until Pius died.

Marcus Aurelius was crowned Emperor on March 7, 161 A.D. His reign was characterized by war, disaster, and intellectual thought. There were three great external conflicts and Marcus dealt with all of them effectively. He won a victory for the Empire in 163 against the Parthians who had invaded Armenia; he coped with a great plague that swept the whole Empire; and he successfully pushed barbarians off Roman soil in the Marcomannic Wars. Internal problems were due to financial weakness, caused by extensive military campaigning that was forced upon the Empire - and he dealt with these problems by extensive government reforms. There were crises in his personal life: his wife was notorious for sleeping around and his heir lacked all the leadership skills for which Marcus himself was famous.

Marcus Aurelius faced and conquered many problems through the strengths that he found in Stoic philosophy. These beliefs are expressed in his Meditations, where he discusses the tensions between his position as Emperor and his feelings of inadequacy. The 12 books making up this set are the most introspective of any ancient philosophical writing - so much so, that they could be called a diary. Marcus was consoled in his writings by the fact that life is short and the spirit, the only thing valuable about a person, is reduced into the universe at death.

[3]

Martyr - A person who dies for the faith, who dies rather than apostisize. (Apostasy [Greek: apostasis, a standing-off] A total defection from the Christian religion, after previous acceptance through faith and baptism.)Martyrdom is part of the Church's nature since it manifests Christian

death in its pure form, as the death of unrestrained faith, which is

otherwise hidden in the ambivalence of all human events. Through martyrdom

the Church's holiness, instead of remaining purely subjective, achieves by

God's grace the visible expression it needs. As early as the second century

A.D. one who accepted death for the sake of Christian faith or Christian

morals was looked on and revered as a 'martus' (witness). The term is

scriptural in that Jesus Christ is the 'faithful witness' absolutely

(Revelations 1:5; 3:14). -Karl Rahner, Theological Dictionary

By martyrdom a disciple is transformed into an image of his Master, who

freely accepted death on behalf of the world's salvation; he perfects that

image even to the shedding of blood. Though few are presented with such an

opportunity, nevertheless all must be prepared to confess Christ before men,

and to follow him along the way of the cross through the persecutions which

the Church will never fail to suffer. -Constitution of the Church, #71

[4]

Felicità (Felicity) – Rich widow whose 7 sons were martyred in front of her just before her own execution. Died martyred in 165 A.D. at Rome; buried beside the Via Salria[5]

Sons/brothers - in some descriptions not all of the seven young men are brothers to each other, nor are they all sons of Felicity, whereas in others they are all related.[6]

Felicità (Felicity) - in some descriptions Saint Felicità was said to have been a slave, in others a noblewoman.[7]

The gens Claudia was one of the oldest families in ancient Rome, and for centuries its members were regularly leaders of the city and the Empire.[8]

Magistrates – were judges (both civil and military) who held powers of life and death; there were various different levels of power, higher ones ruled over lower ones; the Emperor ruled over them all.[9]

Cuirass – protective armour-plate; plate of body armour, the shell-like covering for chest, flanks and back; worn by Roman Legions; at first made of leather, later of metal.[10]

Prefects - were the heads of the provincial administration. The exalted position of the Praetorian Prefect was marked by his purple robe, which was the same as that of the Emperor except it was shorter, reaching to the knees instead of to the feet. The Prefect’s large silver inkstand, his pen-case of gold weighing 100 lbs and his lofty chariot, are mentioned as three official symbols of office. On his entry, all military officers were expected to bend the knee, a survival of the fact that originally his office was military not civil.[11]

Scourge - According to custom, the Romans would scourge a condemned criminal before he was put toSometimes the Roman scourge contained a hook at the end and was given the terrifying name "scorpion." The criminal was made to stoop which would make deeper lashes from the shoulders to the waist. According to Jewish law (discipline of the synagogue) the number of stripes was forty less one (Deut. 25:3) and the rabbis reckoned 168 actions to be punished by scourging before the judges. Nevertheless, scourging among the Romans was a more severe form of punishment and there was no legal limit to the number of blows, as with the Jews. Deep lacerations, torn flesh, exposed muscles and excessive bleeding would leave the criminal "half-dead." Death was often the result of this cruel form of punishment though it was necessary to keep the criminal alive to be brought to public subjugation on the cross. The Centurion in charge would order the "lictors" to halt the flogging when the criminal was near death. In ancient Rome crucifixion was almost always preceded by the "flagrum" and thus it made the vision of the crucified criminal all the more dreadful. Cicero called crucifixion the "extreme and ultimate punishment of slaves" (servitutis extremum summumque supplicium, Against Verres 2.5.169), and the "cruellest and most disgusting penalty." (crudelissimum taeterrimumque supplicium, ibid. 2.5. 165.) and Josephus called it "the most pitiable of deaths." (Jewish War 7:203.)

[

12] Corso – the main road

[13]

Conche = plural; singular = conca – a receptacle made of terracotta or copper, with two handles, used especially in olden times to collect water from the well, spring or river, usually carried home on the head, and then used to store the water in, for drawing out as needed in the home.[14]

Peplo – originally used in ancient Greece, the Romans adopted the Peplo, an item of women’s clothing, worn especially by the

© Amici di Torricella

Translation courtesy of Dr. Marion Apley Porreca