The Legend of Baron Corvo has Re-emerged Together with the Restoration (of the church)

By Gianni Materazzo

Following

restoration works[2] completed in 1996, the medieval castle of

Roccascalegna has returned to life and has now become a museum, an

exhibition hall and a place for meetings and open-air displays. It had been

uninhabited for at least three centuries and had it not been for the

providential and wise intervention of the local administrators, it would

have become a ruin incapable of being repaired. No trace would have been

left, therefore, of this ruin, which stands out from a rugged spur of rock

and that we Torricellans were used to gazing at in fascination every time we

travelled up and down the road to Rocca. This is the common destiny of many

buildings from the past, of great artistic and historic value, which often

is due to the carelessness and ignorance of the administrative councils

governing the Town Halls of the zone; they have allowed these places to

deteriorate or even have decided to knock them down in order to build in

their place squalid, "modern" buildings. Torricella Peligna knows something

about that!

Following

restoration works[2] completed in 1996, the medieval castle of

Roccascalegna has returned to life and has now become a museum, an

exhibition hall and a place for meetings and open-air displays. It had been

uninhabited for at least three centuries and had it not been for the

providential and wise intervention of the local administrators, it would

have become a ruin incapable of being repaired. No trace would have been

left, therefore, of this ruin, which stands out from a rugged spur of rock

and that we Torricellans were used to gazing at in fascination every time we

travelled up and down the road to Rocca. This is the common destiny of many

buildings from the past, of great artistic and historic value, which often

is due to the carelessness and ignorance of the administrative councils

governing the Town Halls of the zone; they have allowed these places to

deteriorate or even have decided to knock them down in order to build in

their place squalid, "modern" buildings. Torricella Peligna knows something

about that!

We must give credit to Roccascalegna’s Mayor and his collaborators,

who, with genial and courageous initiative, finally not only have taken

steps to save what remained of the old castle, but also to completely

rebuild it. They used the same patient, scrupulous care in repairing the

building as was used originally in its construction over the centuries. Now,

when we go on a visit inside (the castle) or simply observe its profile, we

can admire in its entirety the massive turreted structure, which rises above

a perpendicular cliff, including the tower which had collapsed in 1940. This

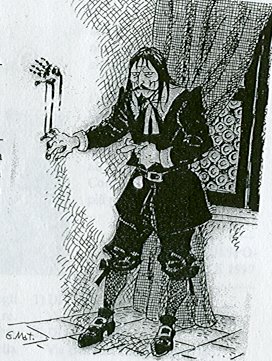

tower is associated in popular tradition with the "bloody hand", or rather

the shape of a bloody handprint, said to have been left on a wall by the dying Baron. He was stabbed to death

(by a young bride) in order to bring an end to the hateful custom of "jus

primae noctis[3]" (meaning right of the first night). Some said

this was a natural tribute required of any bride unable to pay the marriage

tax. Tradition places this matter (the stabbing) in the times of the Corvis,

that is during the 17th Century.

said to have been left on a wall by the dying Baron. He was stabbed to death

(by a young bride) in order to bring an end to the hateful custom of "jus

primae noctis[3]" (meaning right of the first night). Some said

this was a natural tribute required of any bride unable to pay the marriage

tax. Tradition places this matter (the stabbing) in the times of the Corvis,

that is during the 17th Century.

This gloomy legend refers to a certain Corvo de Corvis, who was stabbed to death with dagger blows in the tower of that manor where he used to introduce the brides, arrogantly defined as "tuccarelle" (dialect) ("tacchinelle" = Italian = his little turkey-hens) in order to exercise his "cunnatico" (deflowering?) rights. Since that day it has been claimed that on certain anniversaries a hand dripping with blood appears on the wall of the hall. This thesis, however, has always been denied any historical basis, both regarding the name and the year of death of the man concerned, although there is some doubt as to how he did die; Giuseppe de Corvis, the true feudal Lord of Roccascalegna, died on 28th November, 1645 and he is buried in the local Church of San Pietro Apostolo[4] (St. Peter the Apostle). In order to evaluate the facts objectively, we should also add that in those times the Lords actually lived in their little fortress, which they had tried many times to adapt into civil living quarters and it was only much later, with the advent in 1718 of the Nanni (family of Lords) that they actually moved into the Baronial Palace in the centre of the village.

Beyond all these conjectures, believable or not, the fascination with the sinister story of the Baron Corvo continues to waft in the air around the castle at Roccascalegna. Now after the imposing restorations and the reconstruction of the tower, where the arrogant little Lord was assassinated, who knows whether the bloody hand might not reappear?

Translator's notes:

|

|

|

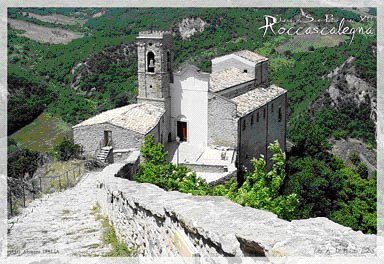

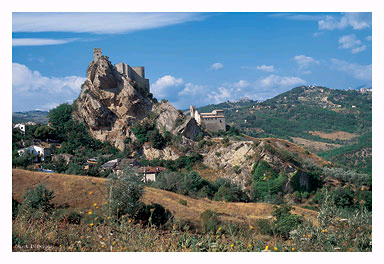

Roccascalegna, its castle at the peak, and the Church of San Pietro below, right |

Chiesa San Pietro Apostolo |

[1] Roccascalegna –

is a small village in the Abruzzo region, in the province of Chieti, about 30 Km from the Adriatic Sea and 15 from the Majella Mountain, between the Sangro and Aventine rivers. It lies at 455 metres above sea level, on the side of a precipitously steep, rocky, sandstone hill and dominates the River Secco Valley, (a river that flows into the right bank of the Aventine River).There are the remains of its medieval castle, with perimeter walls, four Norman round towers and an earlier, Longobard square tower. From the castle and the village one looks out over splendid panoramic views of the lake, Lago del Sangro (locally known as Lake Bomba) with its huge dam. Roccascalegna is hidden from the view of the main valley of the Sangro by surrounding smaller hills, Colle Cicerone, Colle Buono and Colle San Pancrazio.

In the 8th - 9th Centuries A.D. the village was colonised by the Benedictine Monks who founded an important Monastery; the Church of S. Pancrazio still has remains from the 9th Century Benedictine Abbey. After the Norman invasion of the 11th-12th Centuries, Roccascalegna maintained its prestigious position due to the imposing turreted castle which was built in 1250 by Gualtiero Palearia, to defend the village, the valley below and the rich pastures above. In the 15th Century the feud was given first to Raimondo de Anichino, then to the Gualtieris of Manoppello, the Orsini, the Carafas and the Corbos (Corvis) of Sulmona. In the 18th Century it was owned by the Croce-Nanni Barons.

[2]

the restoration was begun about 1985 and took over 10 years to complete.[3]

The jus primae noctis (Latin) meaning "law (or right) of the first night" (or droit du seigneur (French) meaning "the lord's right") is the purported right of the lord of an estate to deflower its virgins. In the European late medieval context, there was a widespread popular belief in an ancient privilege of the lord of the manor to share the wedding bed with his peasants' brides, especially the daughters of his vassals.Symbolic gestures, reflecting this belief, were developed by the lords and used as humiliating signs of superiority over the dependent peasants in the 15th century, a time of diminishing status differences.

Actual intercourse in the exercise of the alleged right is difficult to prove, and there is no hard evidence to suggest that it ever actually happened. However, the symbolic gestures can be best interpreted as a male power display with a basis in the psychology of coercive social dominance, male competition, and male desire for sexual variety.

[4]

Church of San Pietro Apostolo - lies at the foot of the steep, many stepped pathway leading up to the entrance of the medieval castle at Roccascalegna.© Amici di Torricella

Translation courtesy of Dr. Marion Apley Porreca