|

Here is an

extract from a letter that Giovanni Pascoli sent to Vincenzo Di Paola.

“You are not

just a Headmaster, you are a gentleman. With whomsoever I speak, and I

speak with people who come from one end of Italy to the other, they all

affirm my conviction that a gentlemanly headmaster, strict yet good,

forceful yet courteous, is a very rare sight indeed and this rarity I

myself have seen, in faraway Basilicata. I beg you to be patient; and to

show forbearance; and to wait until I return from Viggiano[2]

for the other 43 Liras that I owe you. I say forty-three, but I believe it

is a bit more than that, and I beg you also for this: to tell me the

precise sum. I would not able to go on my journey, if I were to give it

all to you; nor would I even be able to get there. I would need to turn to

others, but without much hope of being satisfied. I have always counted on

you; on you whom I offended the other evening, seriously and mistakenly.

But you see; I don’t think or see anything other than destitution, and my

heart becomes impoverished and weakens my intellect. I too would like to

enjoy things: and, if you could read inside me, you would find nothing

other than that the enjoyments, that I have always waited for in vain, are

only of a very low order. Altogether I am irritated, disheartened. And I

do and say things that I ought not to have done or said. Thus I beseech

you to forgive me not only for the bad things I said the other evening,

but for that of so many other times. I am also returning your books to

you. Do you remember the Fedone[3]

- I never had it at all this year. With gratitude and affection, Yours

most affectionately, Giovanni Pascoli.”

Vincenzo Di

Paola went to Livorno to become Director of Education and he met Giovanni

Pascoli there, when he taught from 1887 until 1895.

“The hardships

and privation” of Giovanni Pascoli continued in this part of Italy too and

so on top of his teaching [in school], he had to dedicate many hours to

private tutoring, which drastically reduced the time available for him to

devote to his studies and his poetry. As we know, it was in this period

that Pascoli began to achieve fame as a poet and he met many scholars and

poets of his times, amongst whom was Gabriele D’annunzio, considered to be

“his younger and older brother” <since he was older by 8 years but less

well known than the Abruzzan poet>. Well, even here at Livorno the

Torricellan, Vincenzo Di Paola, showed his benevolence towards Pascoli, by

making him “take part in the Commission of twenty secondary school Latin

teachers who were called to Rome by the Minister of Public Instruction, to

<discuss the very subject of Latin>”. This event evidently strengthened

even more the bond of friendship between Di Paola and Pascoli, an “intense

friendship and spiritual closeness” that led Pascoli to visit Vincenzo Di

Paola many times here in Torricella Peligna. Di Paola lived at 1, Corso

Umberto, in the house of his relative Maria Di Paola, reached via the

doorway shown in the photo above and now well-known by everybody: Giovanni

Pascoli passed over that threshold many times.

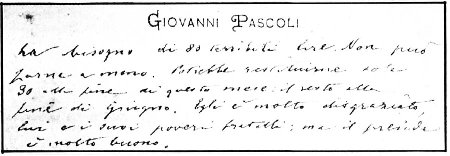

THE Note above:-

Giovanni

Pascoli

ha bisogno di 80 terribili lire. Non puo’ farne a meno. Potrebbe

restituirne sole 30 alla fine di questo mese: il resto alla fine di

giugno. Egli e’ molto disgraziato, lui e i suoi poveri fratelli; ma il

preside e’ molto buono.

Giovanni

Pascoli

needs 80

terrible liras.

He cannot manage without them. He could repay only 30 at the beginning of

this month: the rest at the end of June. He is very wretched, him and his

poor brothers: but the Headmaster is very good.

Endnotes from Translator:

[1]

Giovanni Pascoli (1855-1912), Italian poet.

Pascoli's

childhood was marked by a series of tragedies; he was 12 when his

father was murdered and this was soon followed by the deaths of his

mother - who had a deep influence on his life, his vision of the world

and his poetry - and five of his brothers and sisters who died young.

A radical in his student days at the University of Bologna, he was

subdued by imprisonment (1879) and then gave up his political

activities. After completing his studies he taught classics,

succeeding Giosuč Carducci as professor of literature at Bologna in

1905; but never abandoned his main passion: poetry. His large

collection of tender poetry, written in pastoral style, won him

international fame; many verses were inspired by memories of his

family. Also seeing his mission as the chronicling of Italy's glory,

he wrote of historical and patriotic subjects, earning D'Annunzio's

epithet "the last son of Virgil." His works include Carmina (in Latin,

1914); the more mystical Myricae (1891-1903); and the patriotic Odi e

Inni (1906). Pascoli remains one of Italy's best-loved poets. He was

also an essayist of distinction.

|