IN 1919

IN 1919

When I told Margherita, a colleague of mine from school, that I was from Torricella, she couldn’t believe her ears. It didn’t seem possible to her that anyone other than her mother could ever have spoken about Torricella.

So she told me that in conversations with her mother she had continuously heard fairytales about this "extraordinary world".

I didn’t let the occasion pass by without asking Signora Fadelli to tell all of us "Friends of Torricella" about her experiences and to paint a picture for us of Torricella in the 1920’s.

Gabriella Porreca

On the left Mrs Fadelli’s house, (possibly the marked one).

On the right, in front of A. Porreca’s shop, the houses of the chancellor, the dressmaker and the jeweler.

Two "respectable" people taking a walk: maybe the Doctor and Don Carapella.

By IDA FADELLI

Preserved from the various vicissitudes of life and the calamities of the last war, I have in my house an almost intact box with a faded label several tens of years old, that says "Little Unthought-of Things". Many of these concern my childhood and amongst them is a postcard that my father sent me early on in his stay in the Abruzzo when, as an army officer responsible for requisitioning grain, he served during the 1915-18 war.

At the beginning he was at Francavilla for a short while and then at Ripa Teatina, from where he sent the postcard relating to that period. A keen, extrovert officer from the North, in visiting the vast zone assigned to him, he came across the village of Torricella Peligna and he was so struck by the extraordinary hospitality of its people that he decided to stay there for the entire duration of his job.

After about a year, since the emergency war situation did not seem to have any immediate end, my father wanted us to be with him, so my mother and I left Milan to join him. It was July.

The train journey lasted all night; I awoke at dawn and my first wonder was the sea. Then we went from Lanciano to Casoli where my father was waiting for us. At Casoli we climbed into a carriage which the coachman called a "bellows" because it had a dark leather cover which he lifted up like an expanding shower hood. That stretch of road going towards the mountain with such an unusual means of transport was unusually fascinating for a child: the green landscapes of the countryside in summer opening up before my eyes remain with me like an indelible memory.

But even stronger is the memory of the moment when first I awoke in Torricella, the next morning. I was roused by trumpeting sounds and animal noises, bleatings and gruntings that, coming from the city, I’d never heard before, an absolute novelty, certainly a great curiosity. But soon I was distracted by something else: shouting, at first distant and confused, then more and more dominant and distinct, which made me look out of the large window of the new house that was on the main street. Beneath, along Corso Umberto I, was a large market. It was the feast day of San Marziale, who, if I remember rightly, is the town’s patron saint and also of Santa Felicita. Underneath our windows there were ceaseless comings and goings. I remember lots of colours and words which sounded so loud to me, in that dialect which I found incomprehensible. Later came the never-ending procession. And the saint’s statues: an enormous San Marziale and a smaller statue with the sweet face of Santa Felicita. Inserted into the effigies’ clothes and secured with safety pins were offerings of gold and money, which embellished the shaky statues. The women wore costumes and carried shiny conche (copper vessels for carrying water or grain - typically balanced on one's head) on their heads, decorated with ribbons and flowers and filled with grain. They walked with perfect equilibrium; their dignity and solemn gait astonished me almost to the point of forgetting to look at the beauty of their characteristic costumes, the richness of their flashy earrings and their gold necklaces gathered by pins in long rows on their bodices. Some old men, wearing distinctive shorts, buttoned to the knee, leaving their long white socks uncovered, were marching in front of the Municipal band. In the middle of the procession a canopy protected the priests who were displaying the Holy Sacrament. As they passed people sang solemn religious songs.

That first unforgettable day had ended, but others were yet to come.

The apartment which two unmarried old ladies, certainly of ancient nobility, had rented to my father had a huge living room with frescoes. The kitchen overlooked a narrow street with very modest single story houses, beyond which the eye wandered over an expanse of green and yellow fields. Down there in the distance, as far as the horizon, one caught sight of a green-blue line: the sea. It was the Adriatic, that I had seen on my journey: from my window more than seeing it one had to imagine it, but to my childish fancy it was the sea, something remarkable and new.

The beauty of these places’ returns to my mind in marvelous pictures in which static nature does not exist: I see again unripe corn moved by the wind in boundless fields which themselves seemed to be stretched out by seawater; flowering almond trees that gift the grass beneath with the purity of a few petals; tufts of intensely yellow juniper; marvelously enthralling flights of butterflies against the wild panoramic background. In the air the never-again-found perfume of certain wild pale carnations, facing brown crags. I spent that stupendous summer together with my newfound little friends enjoying the healthy mountain air of the village, discovering the most beautiful pathways, gathering the sweetest of blackberries, listening to the peasants’ songs at harvest-time, awaiting the evening, the moment to run to the end of the village against a myriad of fireflies, the last great magic before sleep.

The autumn came and the glow-worms by the hill of the "Calvary" went away. I waited with sadness for the day when we would have to return to Milan but they didn’t talk about going back. The war continued and they thought of staying. Thus – happily – I went to the third elementary class of the village school with Mrs. Murri the elderly teacher: and then the start of the fourth year with a sweet teacher, the mother and aunt of dear friends. I remember her elegant, slightly sad face. Her name was Marianna D’Annunzio. The names! How many names come back to my mind. Those of the morning register in the third class: Antrilli, Aspromonte, Carapella, D’Antonio, D'Ulisse… Piccone, Porreca, Sabatini… Of the children I recall two affectionate sisters, my desk-mates, who had come back from America, daughters or nieces of the owner of the Italia Hotel. The elder, Maria helped me with divisions, I corrected her dictation. Maria D’Ulisse, a very beautiful dark girl with big black eyes who came from a large farmhouse a long way away, wore the local costume with a "fazzuolo" (head-scarf) and "ciocie" (laced sandals) tied at the ankles with string. I wondered how she managed to get to school: maybe on a mule. There, in those days, the mule was the most commonly used means of transport.

The boys were on the other side of the long desks. I remember Gianni Contini, son of the clerk of the court, who came from Parma; a certain Dante, with blond hair, a very good and sensible boy, I think he was the son of a magistrate. And Carmine, Ulisse, Marziale who came from the countryside and so could not attend during the cold months. Marziale was a strong boy who did not know how to read but had firm shoulders and could carry sacks of corn bigger than he was.

I liked the customs of the village in which we stayed. There was the olden use of titles: Donna Giuseppina, Donna Carmela, Donna Maria…. Then there were the "Dons". Don Pippo, Don Peppino, Don Raffaele. Maybe they were acquired rights, those "Dons", or maybe it was only deference from the others: they certainly had their own precise significance, that of respect, sometimes even towards goods, but certainly towards people. But these are reasonings made with hindsight: then all those "Dons" roused my curiosity and they amused me simply because I heard them ringing in my ears like the tolling of bells.

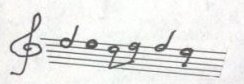

I liked everything about Torricella: long walks to the "Ciferine Stones"; the Corso with its unusual shops – I recall one in particular, whose owner, Antonio Porreca had several children; the conversation lodge, just under my house, where the town’s authorities met to play billiards; and finally the old houses, sheltering in the high part of the town, where the poorest peasants used to eat polenta and un-dressed salad. But if I happened to pass by they always said "Favour us, Miss, would you like some?" I really liked everything: the afternoon snack of homemade bread spread with oil and salt; "guitar" spaghetti (alla chitara), the local cake "il fiadone". Every thing had a new flavour and was a fresh discovery. Even thoughts about the wolves that, when it snowed, came down hungry right into the town from the Majella, did not make me afraid and in the morning I would look inquisitively at their footprints in the freshly fallen snow, whilst I listened to the adults’ stories telling that, at the nuns’ house, the first on the road to Gessopalena, the wolves had carried out a massacre in the chicken-house.

For having learnt to rejoice in nature’s beauties, for having known a poetic world of extraordinary customs and songs, for everything that was offered to me, with love, friendship and simplicity, I would like to end by paying homage to this village and its hospitable people. I began these lines by mentioning my father, so it seems to me to be only right that I recall him again here at the end, with the words that I found in some of his notes, that he himself quoted the night of our leave-taking dinner, at the Hotel Italia of course, with all those who had loved him during his stay. I see him with the eye of recollection, raising his glass to make a toast after having mentioned each of those present by name, one by one, and saying "….. let us all repeat together with fervid speech/ Long live those who go and those who stay! Hurrah for Torricella!"

© Amici di Torricella

Translation courtesy of Dr. Marion Apley Porreca