| GETTING WARM |

' ' |

|

|

Ricordi di Torricella

Memories of Torricella

| GETTING WARM |

' ' |

|

It was an evening at the end of October and it had been night for

a while. Outside the air was damp and cold and it seemed to grip our “massarì”

(country house with cultivatable land adjoining it) in freezing bite. Inside we

could hear the crackling as the wood burned in the hearth. The heat that it

released, with difficulty, warmed the air a little, brought the pan of beans to

the boil and at times sent flashes of a warm yet tremulous light towards my

grandparents who were discussing things that seemed to me to be mysterious and

important. In the end, which rarely happened, they reached an agreement: I was

to join in too. After dinner, my grandfather said: "tomorrow we must get up very early". The next morning, before the cocks had begun to crow and before the dense black of night had even begun to clear, my grandfather came, as he usually did, to shake my arm and wake me and he said to me: “ema i” (we have to go). I had tossed and turned in my cold bed before falling asleep and on awakening it seemed as if I had only just fallen asleep. Getting out of the bed that had finally warmed up, I felt as if I were leaving behind a part of my own body. I got dressed. I went over to the hearth where a lively flame was attempting to bring warmth and light to the room, where my grandmother was making cheese and she was also warming some of the freshly milked goat’s milk for me. | ||

|

|

|

|

Grandmother at the fireplace of the house in Torricella |

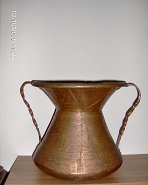

the conca |

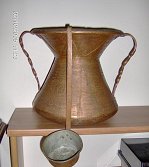

the conca and the ladle |

|

As soon as grandmother saw me she immediately stopped what she

was doing, came over to the table, on which the conca of water held pride of

place, and beckoned me over. So that I could wash my face and wake myself up

properly, grandmother drew cold water with “lu maner” (a large copper ladle)

from the conca and let it fall into a wash tub that was on the floor near the

conca. I stretched out my hands to catch the cold water as it fell and washed my

eyes and my face. After drying my face I was ready to eat my breakfast of

warmed goat’s milk into which I dipped the pieces of bread from a large “fella”

(slice) from the “panelle” (rustic cob-loaf) that grandmother lovingly made

every fifteen days in the oven next to the fire. The genuineness of the food and

my hunger made that breakfast all the more delicious. My grandfather said: “get the hatchet, but this morning you must also get the big one: the one we sharpened last night. Also get the long rope.” We set off, obviously on foot, in a direction that I didn’t know. It was still darkest night, without any stars or a moon; the sky was covered with threatening black clouds; the air was cold and damp and it seemed to sneak into your clothes, almost as if to stroke you icily which would suddenly set off cold shivers all over your body. The crunching footsteps, made me imagine that a heavy frost had covered the world all around and it seemed that all forms of life had stopped as if waiting for some mysterious event. I followed my grandfather’s firm footsteps without being able to tell how he was able to find his way in that thick darkness.  We walked at a good pace to try and beat the cold from which the poor clothes we wore, our shoes and our “coppole” (a type of cap – see boy in photo) were barely able to defend us, I could feel the cold steel blade clutched to my shoulder: the large hatchet; I felt proud to have been authorised to carry it today; its weight was tiring, but I was so proud of the responsibility that had been given to me. In this frame of mind I looked into the darkness, but in vain, trying to see anything I could recognise that would tell me in which direction we were going. We walked on in silence, we were almost swallowed up in the darkness which surrounded us. After having gone uphill past some fields, we crossed a field going downhill and as we walked downwards the dampness in the air became thicker and colder. By now we had been submerged in that black, cold night that seemed never-ending, when the darkness was broken by a faint light in the distance, which seemed at times to appear and disappear; the light was so feeble and flickering that I began to wonder if there really were any light at all. We carried on walking ever more decisively towards that which might have been the only living point in the world that surrounded us. We still carried on walking towards that light and even though it continued to flicker, I no longer had any doubts about its existence. A little bit further on, my grandfather said that it must be the hearth-light that we could see through the little window of the “massarì” belonging to “Cumpa Mingo” (“compare” Godfather/old friend Domenico), but that he had not expected to find him already awake. Even before we knocked, the door of that poor little dwelling lost amongst the fields, opened, “Cumpa Mingo” appeared, greeted us warmly and asked us to come in by the hearth. On seeing me, our host told my grandfather off in a kindly way for having brought “lu cuadrale” (the child) despite the night and the cold. I felt such pride in those few words because, on that dark, cold morning, for the second time I was being treated as a man and not as the child that I was. I had the impression that after our long journey in the cold and in the night, we had reached a safe refuge where we could restore ourselves, having been tested by an experience that was most unusual for me. The heat from the chimney weakened the cold that by then had insinuated itself right to our bones; my face, my hands, my feet and my ears began after a while to regain their functions. Whilst “Cumpa Mingo” got ready to accompany us, his wife prepared plenty of hot coffee which she generously offered us; naturally it was barley coffee, from the very barley which this same wife had planted, cultivated, harvested, threshed, dried, toasted, ground and finally used to offer freely and generously to us. Quite apart from the pleasure of the hot drink, in that universe of coldness, I really appreciated that gift as if it were a part of the very life of the mistress of that poor house, for although she served the coffee in rough and ready cups, her attitude, her smile and her genuine country courtesy, emanated directly from her heart. Oysters, caviar and champagne, that were offered to me years later by wealthy friends in a sumptuous locale in Paris gave me far less pleasure than that which I felt for that coffee, in front of that hearth, offered by that poor lady. “Cumpa Mingo” told us that his brother would also be coming with us and so after a little while the four of us set out. The blackness of that night had lifted a little; after we had walked along another uphill road, I finally realised the direction in which we were going: after a long deviation towards the hamlet of “maluvent”[1] we were going towards “Lu munt” (Mount San Giuliano). After we had walked much further we turned right; but we were no longer going towards “Lu munt” but rather to a flat zone to its south. In the poor light that began to filter through the thick blanket of clouds, we could see all around us the silhouettes of widely-spaced grandiose trees of all sizes. Soon after we heard the shouting of three other men as they approached, who greeted my grandfather with that deference and consideration that everyone used, in those now vanished civilised times, when speaking to someone older than themselves. | ||

|

Soon after we heard the shouting of three other men as they

approached, who greeted my grandfather with that deference and consideration

that everyone used, in those now vanished civilised times, when speaking to

someone older than themselves. Then they asked my grandfather, modestly and courteously, which was the choice for this year. Grandfather made a sign for us to follow him and after a while, without any hesitation, he said: “uan chesta a ec” (this year this one) indicating a majestic oak that seemed to reach the sky with its foliage. The men got themselves ready. They secured the tools that they had carried with them at the foot of a large oak tree: hatchets, like the one I was carrying, hoes, pitchforks, saws (one with a long blade over two metres in length with wooden handles at each end); on one of the branches of the same tree they hung a small basket with the food for lunch, “Lu cecine” (a special terracotta container) with water to drink and “lu vasciellucci” (in the shape of a small barrel that held a few litres) full of wine. |

| |

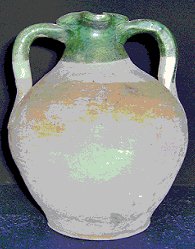

"Lu cecine" |

|

“Lu Cecine”: the four small spouts on which one could rest one’s mouth for drinking and the mouth of the bottle shaped for filling it without the need for a funnel |

| Not one of them, however, removed their tobacco, their “cartine” (cigarette papers) or their respective “ppicciarelli” (wooden matches).  Those who had not already worn them since leaving home, now put on their “L chioche” (special footwear made of goatskin which were worn over very thick, hand-knitted lambs-wool socks, which barely covered the soles of the feet and were secured by long strings also made of goatskin). The boy in the photo on page 2 wearing the cap is also wearing “chioche”. Then the five men began something which seemed to be some sort of a ritual that they had already repeated many times over. They acted calmly with no uncertainties, each one carried out his own duties, seriously and competently, without tripping up or uselessly wasting their strength. Having evaluated a whole series of circumstances, three of them went to the foot of the chosen oak and began to dig the earth, searching for the roots to be cut; which took place almost exclusively on the western side of the tree. The work was made harder by the clayey soil which was wet and stuck to the tools but not to the men’s “chioche”: this footwear was ideal for moving about in the wet, muddy terrain. Another difficulty was caused by the stones mixed in with the earth, which prevented the tools from penetrating in depth. Immediately afterwards, the other two men came in and took over from the other three, thus taking the work forwards and also allowing the men to regain their energies and to last longer despite the heavy work required. Day was slowly breaking and on the western side of the chosen oak tree an ever deepening hole was forming. At about ten o’clock (no-one had a watch; we judged time by the light and by experience), we took our first meal-break. Everyone sat down as best they could and began to eat bread, cheese and “cacchie d saicicce” (some slices of sausage) all accompanied by water and wine; in the same way as the work was carried out, without any delay or anxiety, so the meal took place and it ended with a smoke: some used a terracotta pipe, some smoked cigarettes, obviously after completing the none too easy job of rolling them with their hard callused hands. All this while I had remained more or less without any work because I was not judged able to do that sort of work; which was the reason I was feeling so disappointed. Whilst waiting I watched closely everything that was taking place; I listened to the men’s discussions without interrupting; I delighted in the throbbing all around of uncontaminated nature; I listened to the echo produced by the blows of the hoe and the hatchet that the men were inflicting on the feet of that oak tree. I was fascinated by those grandiose trees surrounding us; in particular, the small branches and the leaves seemed to me to be an unmistakable example of the beauties and mysteries of life (many years later I learned that these were used to make the crown of Giove[2]). Whilst waiting, however, I had formed a list of questions. I made use of the meal break to try to get some answers from my grandfather. Grandfather why did you choose that oak tree?  Because this zone, which is altogether very large, is partly my own property and because it has always been used to provide wood for our family’s use; there are about thirty oaks and each year when we cut down one of them we make sure that we grow a new plant, taking great care that the remaining trees will be able to provide wood for the next 30 years. We have always done it like this and we have never lacked wood for our family and it will always continue to be like this provided our descendents, in their turn, respect the rule. Why wouldn’t they respect the rule? Because there is always a temptation: to cut down more than one oak tree a year in order to sell the wood and pocket the money which could be useful for so many things; but if you fall into that trap there will be people in the future who won’t be able to keep themselves warm, who won’t be able to gather the acorns to feed to the pigs; this stony soil that is so good for oak trees, is not suitable for agriculture; if you don’t give the oak trees sufficient time to  grow, instead of a beautiful forest, with time there will just be arid,

useless land.

grow, instead of a beautiful forest, with time there will just be arid,

useless land.Grandfather why are these men helping us? There are many jobs that are much more difficult and sometimes impossible if you have to do them on your own. Moreover if you work alone you can’t avail yourself of everyone else’s abilities and experience. Anyhow we aren’t paying them, in the way you might think. From time immemorial we have always helped each other, so everyone works for everyone else, not to be paid in money, but relying on help being available in return when there is the need. While we are working we don’t consider how much time must pass before the day’s work is done. We work with complete disregard both for the hours and for the work. Today, for example, we are working to cut down our oak tree; the quicker we do it and to the better it is done, is in the interests of everybody taking part, therefore everyone generously gives of his best. They are not our workmen and we don’t treat them as such but with the same consideration, respect and dignity as they show to us. We are all people who help each other. As you’ve been able to see the work is undertaken with seriousness and composure. We chat as we work. We talk about our experiences, our joys, our woes. We talk with the same confidence and trust as one speaks to a friend. During the day, together, we have two snacks and an abundant meal, offered by the master of the house for whom we are working that day. This has nothing to do with the work in the mines or in the factories like I carried out so laboriously in America. Here there is no high-handed presence of a boss, or anyone serving him, nor any of the advantages that go with that situation: in practice the earning of even more money. Here we all live in order to live, not to accumulate wealth. Remember, he added finally, that today these people are helping us; even you in your small way, so, should it happen you will have to give generously of yourself to help them with something if they should ever need it. Several months later, whilst we were all closed in our houses beneath a deep blanket of snow, close to the hearth, in the heat produced by burning that oak tree, I taught the rudiments of reading and writing to the youngest two of those men, who had never been able to afford the luxury of going to school. With the same calm manner in which he had eaten, spoken, drunk, discussed and smoked, he went back to work again. The men who were still digging on the western side of the foot of the oak tree came upon the largest roots; using the hatchet they chopped through them and separated them from the stones they came across and from the muddy soil, which they threw far from the tree with their hoes. In this phase I was given the job of gathering up the pieces of root they extracted and piling them up at a distance from the oak. In going to and fro the soles of the boots I was wearing became thicker and thicker as the muddy soil and stalks of dried grass stuck to them. The physical hard work this caused meant that every now and again I had to remove the mud that had accumulated underneath my feet; but I felt satisfied because now I too was playing a part in that ritual which had a precise, concrete goal that was totally clear to me and which I myself wanted. Now the grey light of that grey day only stingily lit the people, the things and the animals in that forest in which sleepy nature reigned supreme. The sweat and the wine warmed the limbs of those men, their hollow[3] faces burnt by the sun whose absence was almost justified[4] on this day. Their composed chatting was never-ending, as were the courteous and respectful way in which they treated each other. They treated me with respectful and courteous attention but a curious fact shone through, they were diffident, as if dealing with a complete stranger. In reply, I did everything possible to support them and give them a reason for not treating me differently; this task was difficult because even though I had been born in Torricella, I lived in Rome where I studied and where probably I would return; moreover, I didn’t speak the dialect too well, I did not know about the life they lived; I did not know how to do all those things that people of my age knew perfectly well how to do. Someone let us know that in the distance they could see “Za Filicett” (Signora Felicetta) arriving, my grandmother, with a large “staro” (a type of large, low basket often made with very thin planks, bound together with goatskin laces - “lu stare” in dialect); of course she was carrying it on her head. The sign was evident, it was nearly “mez iurn” (midday) and grandmother was bringing an abundant lunch for everyone; she was approaching at a slow but continuous pace; in order to reach us she had walked without stopping for over an hour with a heavy weight on her head; she carried her load in a natural way without any apparent effort. She had got up before us, had seen to the animals in the stables (cleaned out the dung, put down fresh straw, given them food and water and had milked those that needed milking); she had lit the fire, made the cheese, prepared our breakfasts; after having seen us off, she set the whole house in order; she had filled the water containers by going to fetch water from the well, drawing it out with “lu tragn” (a small bucket tied to a rope) and then filling the Conca and as soon as this was filled she put it on her head to carry it into the house; she had thrown away the dirty water in the washtub beneath the Conca, which had accumulated from the evening before and also from that morning; then she had begun to prepare the lunch; from the chain in the hearth, she hung “nu callar” (a cauldron) with plenty of water in it to boil; she had gathered the wood for this purpose, a bundle of twigs to light the fire and to obtain strong flames though of brief duration (to boil the water) and large robust logs to get a lasting fire that would give charcoal embers which also lasted a long time (to cook the sauce). She had searched for and found the chickens that were scratching around the “massarì”, with an atavistic leap she had grabbed the cockerel that had been reserved for that day; she carried him to a place in front of the front door of the house, where she had prepared a plate and a knife; she held the chicken tightly between her knees; she held his head in one hand and with the other hand she used the knife to make a deep cut beneath the cockerel’s ear; she let all the blood drip into the plate that she had  prepared; when the victim showed no further signs of life she put it

into a basin; she took some of the water that was boiling over the fire

and poured it into the basin containing the chicken; she put the boiling

water over the chicken to make plucking it easier; she carefully plucked

it, de-skinned the feet and cleaned the head and the neck; she passed

the cleaned chicken over the flame in the hearth to remove all traces of

feathers and hairs; she cut off its head and feet and prepared them to

make the soup for the next day; she gutted the chicken; the first thing

she checked for was the gall bladder and making sure not to rupture it

she removed it quickly and expertly and threw it into the rubbish; she

removed all the gizzards from the chicken and cleaned them; she skinned

the gizzards and cut them into pieces; she put them into a small frying

pan with homemade oil, onions she had grown herself and tomatoes that

she had planted, cultivated gathered and preserved; whilst the sauce

began to cook, she put the pieces of chicken into a large frying pan

with other homemade ingredients to stew them; while these were all

cooking, after having prepared the table and the sieve, she sieved the

flour to separate it from the bran; with the white flour she obtained,

she made a ring-cake shaped pile on the table, into which she put the

contents of six eggs that she had gathered from her henhouse; then with

her own hands she had mixed it all; then she kneaded the flour, eggs and

salt together for a long time; then with her rolling pin she made a

layer of pastry that was large and uniform and about one millimetre

thick; she let that dry for a bit and then cut it into squares about

four centimetres each side; all this whilst she kept the fire under

control, cooked the sauce, cooked the chicken, and meanwhile the cat was

attracted by all these good odours.

prepared; when the victim showed no further signs of life she put it

into a basin; she took some of the water that was boiling over the fire

and poured it into the basin containing the chicken; she put the boiling

water over the chicken to make plucking it easier; she carefully plucked

it, de-skinned the feet and cleaned the head and the neck; she passed

the cleaned chicken over the flame in the hearth to remove all traces of

feathers and hairs; she cut off its head and feet and prepared them to

make the soup for the next day; she gutted the chicken; the first thing

she checked for was the gall bladder and making sure not to rupture it

she removed it quickly and expertly and threw it into the rubbish; she

removed all the gizzards from the chicken and cleaned them; she skinned

the gizzards and cut them into pieces; she put them into a small frying

pan with homemade oil, onions she had grown herself and tomatoes that

she had planted, cultivated gathered and preserved; whilst the sauce

began to cook, she put the pieces of chicken into a large frying pan

with other homemade ingredients to stew them; while these were all

cooking, after having prepared the table and the sieve, she sieved the

flour to separate it from the bran; with the white flour she obtained,

she made a ring-cake shaped pile on the table, into which she put the

contents of six eggs that she had gathered from her henhouse; then with

her own hands she had mixed it all; then she kneaded the flour, eggs and

salt together for a long time; then with her rolling pin she made a

layer of pastry that was large and uniform and about one millimetre

thick; she let that dry for a bit and then cut it into squares about

four centimetres each side; all this whilst she kept the fire under

control, cooked the sauce, cooked the chicken, and meanwhile the cat was

attracted by all these good odours.When the water in the cauldron was boiling, one by one, she added the squares of pasta that she had made; when the pasta was cooked she drained it and mixed it with the sauce and she sprinkled over it cheese that she had made and grated by hand; then she prepared “lu stare” wrapping in a tablecloth the forks, a large “vaccile” full of “sagn a pez” (those squares of pasta) that she had cooked, the frying pan with the stewed chicken, bread, wine and water; on top of everything, to keep all the food warm, she placed a heavy blanket made of hemp that she had woven, the thread for which she had obtained from hemp that she had planted, cultivated, gathered, taken to be soaked, purified from the woody part (with the “ciaula”)[5] and finally she had spun them with great patience, as in the saying, with “lu fuse” (the spindle)[6] and “lu vurtecchie” (the fusarole)[7]. [8] |

||

“ciaula” – dialect; Gramola – Italian. |

Women working with hemp separators |

| When she

arrived with this heavy weight on her head she didn’t seem at all tired,

she was serene, calm, greeted and was greeted by everyone with affection

and courtesy; they helped her take “lu stare” from her head and she set

about laying out the lunch on a stony part of the field that was not muddy

and was not very far away from the oak tree; first she laid down the large

hemp cloth, at the centre of which she placed the tablecloth and at its

centre she put the large “vaccile” (large serving dish) with the “sagn a

pez”; near to that she put the frying pan with the stewed chicken; and all

around she placed slices of bread and the forks. All eight of us sat in a circle on the large, thick hemp cloth and we began to eat with an appetite made even keener by the perfumes arising from this genuine food that had just arrived, but above all by the hard physical work in which we had all been engaged and also by the cold that we had been fighting the whole morning. From the faces of these people, from the way they behaved, from the courtesy and reciprocal respect that they expressed for each other, there emerged satisfaction, serenity and perhaps an unconscious knowledge of living in symbiosis with the surrounding Nature and with a love towards all things and all people in creation. These people, who in those days were considered to be ignoramuses by the really ignorant, lived a culture that had been accumulating with ten thousand years of experience and was transmitted from one generation to another almost exclusively by example; a culture which, amongst its other good qualities, did not need any effort and did not create any doubts, when appropriate solutions needed to be found for the countless problems of human existence. As much as I have always been in search of them, I still have not met anybody who, in spite of having at their disposal a fortune, riches, beauty, philosophy, culture, ideology, religion, science, tranquillisers, sleeping tablets, drugs, experience and things of every variety which life might have given them, had had more satisfaction from life than that which was felt by our poor honest peasants. After the meal the men set to work again and my grandmother put all her things together and started off on her way home. I carried on with the work that had been given to me but without neglecting any of the details from the discussions that had taken place. After about two hours we took another break to eat something and to smoke. Then we started work again in the hopes that before we left we would be able to fell that mighty oak tree. They dug a little more and then the youngest of them climbed up the tree and tied the ropes that we had brought with us to the high branches; once he had climbed down, we tried pulling these ropes in a westerly direction to try and make the tree fall down. It was all in vain, however, because the oak tree resisted us. Grandfather why wasn’t it cut with the saw? He replied that if they had done that, they would have lost all the wood from the lowest part of the tree, they would have left both the rest of the tree and its roots in that glade, which would have been an obstacle to the growth of other trees and to the care of the underbrush; this activity was carried out at least once a year and comprised removal of plants growing spontaneously such as brambles, weeds and suchlike and gathering up any dry branches that had fallen from the trees. Grandfather why didn’t we dig all around the tree rather than only on its western side? In order to make it fall to its western side which, as you can see, would not cause any damage to other trees when it fell; and then to dig all around it wouldn’t be of any use because, as you will see when the tree falls, all of the part that is under the ground will emerge. It was becoming night again so we gathered up all the equipment, our personal belongings and each of us set off towards our own homes with an almost tacit agreement that we would have to continue the next day. Very early the next day we continued to dig and shortly before our first breakfast break, the oak tree surrendered. Set off by the pull on the ropes, slowly at first, it moved towards the west side, then ever more quickly it hurtled down to the ground completely filling the glade in a mountain of branches and leaves. The weight of the tree had raised up the roots on the east side and with them the earth and the stones that we had removed with such hard work from the west side. We noticed new smells, shapes and colours in that glade ravaged by the falling of that enormous oak tree. We interrupted our work to have our first breakfast and to their usual discussions they added the giving out of duties for all of us, which from that moment on would be completely different than before. When we restarted work, two men busied themselves with cutting the roots of the east side, taking care, however, to obtain from them and from the part of the trunk joined to them, a heavy mallet (a large two-headed hammer that would be used for knocking “l zepp” {iron and wood wedges with which the large logs would be split}). Whilst I was carrying out the duties assigned to me, I paid attention with great interest to the construction of this mallet. The two men first identified a root that was large enough and straight enough, then they cut the part of it that had gone under the ground. They also cut the end which went towards the trunk, taking care also to cut out a part of the hard, compact trunk; assisted by their hatchets, they transformed it into a hefty cube; they made the root part into a manageable handle; thus the powerful wooden hammer was ready. The other four men were busily sawing the large branches, reducing them to segments about a metre in length. With the small hatchet I cut the branches full of leaves, up to five or six centimetres thick and about a metre and a half in length: I was preparing the material for making the faggots (bundles of sticks) that, once dried, would be used by my grandmother for the domestic fire. They had to be tied up tightly, with special branches of elm, but every now and again my grandfather did this task because then I did not have the necessary strength for doing it. Amongst the leaves, every so often, I found balls about four or five centimetres in diameter, with which I was forming a secret collection. I fantasised a thousand games to play with all those balls which at that time of year were a brown colour. In those moments I did not realise what other types of game were awaiting me. Later on I asked my grandfather what they were and he told me “la maladi di cerque” (the disease of the oaks) but he didn’t add anything else. Very much later on I learned that those balls were called Galls[9] or Cecidium and that they were growths made up of hypertrophic tissue that had developed in the plant as a pathological reaction to the stimulus exerted on them by a parasite, which uses them as a home during their period of development, using them also as a food supply. The large branches that had a diameter of over 20-25 centimetres, were split by the men into two, four, eight pieces or more, depending on their diameter. One of them, with a large superbly sharpened hatchet gave a precise and powerful blow on the vertical centre of the trunk to be split; then withdrawing the hatchet he introduced an iron “zeppa” into the cut and pushed it further in with blows from the powerful mallet that they had just made; as the wedge went further in to the wood, it made an ever deepening split, large and long; then they put in other wedges in the same way until the trunk split into two; this work continued until all the pieces of wood had become of a suitable size to feed the domestic fire. |

|

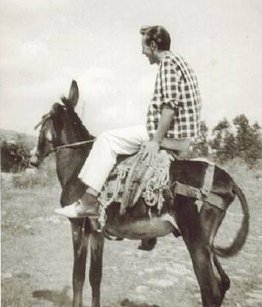

| In reply to a request of mine, my

grandfather explained that you could not use a metal hammer to hit the

wedges because this would have ruined the iron wedges and have destroyed

the wooden ones. When a large pile of wood was ready, they “loaded” the donkey and gave me the job of leading it back to the “massarì” where, together with my grandmother, we had to unload the wood; I wasn’t too happy about it, but they easily convinced me by saying that on the way back, since the donkey would have no load, I could ride him. They gave me a lot of instructions and then let me leave. |

The

donkey has been harnessed with “lu mast” (a packsaddle) for carrying

things and not with a saddle for carrying a person. My weight on him is

unbalanced and he is showing his disapproval. The

donkey has been harnessed with “lu mast” (a packsaddle) for carrying

things and not with a saddle for carrying a person. My weight on him is

unbalanced and he is showing his disapproval. |

| The donkey was large: his body was like

that of a horse. He was black and he was young (you could tell his

exact age by examining his teeth). His long straight ears were always

stretched out so he could be aware of everything that was happening

around him. After a while I realised that there was no use in leading

him; he knew the way better than I did; he accurately chose the path

needing the least effort; since much of the way was downhill, he

didn’t seem to exert himself much, despite the heavy load he was

carrying. I knew that if, according to him, the conditions were not

suitable, he would have brayed in protest and in the worst cases he

would sit down on the ground and refuse to go forward. Nothing of any

of that happened on our first journey together because the men had

loaded him up well: a bearable weight, well balanced on both sides, so

his body would not be hurt by the things he was carrying. Moreover,

before setting off he had been fed and watered. I walked behind him, but not too closely because every now and again he let off intestinal gas powerfully and noisily and he defecated inconsiderately and without warning. His steps were regular and continuous and I was able to keep up with him without any difficulty until we reached the beginning of the hill near the “massarì”. I began to tire and then I had the idea of doing what I had seen others doing so many times, that is to hold on to his tail; other than the risks I have just mentioned, there were no problems: the donkey pulled me up too. When we had nearly reached the fountain of the “calderali”[10], I suddenly noticed that he wanted to be set free and once he was free, he lengthened his stride and then he stopped. Afterwards I realised that he needed to urinate and what is more he had to do it in a certain spot, that is a certain point in that road where all the donkeys that passed by used to urinate; a place which to us humans stank to high heaven, for them held an inalienable attraction. After this obligatory break we arrived at the “massarì”; together my grandmother and I unloaded the wood; I gathered up the ropes with which the wood had been bound and then I was ready to return riding the donkey. Since my grandmother was ready to take the second day’s meal, I suggested that she should ride the donkey; she replied that were she to ride on the donkey she would feel sick; so then I suggested that I should carry some of her heavier things whilst I rode the donkey and that is what we did. On the return journey nothing in particular took place, except that, on seeing some beehives, I asked my grandmother what the bees ate in the winter when there aren’t any flowers and everything might be all covered in snow. She replied, “lu melo”[11]. This reply seemed strange to me; thinking that the bees could eat the apple trees did not seem right. I hesitated a little and then asked her again; rather irritated, my grandmother gave the same reply again. I tried to think that maybe the bees would be able to eat the apples like those we had put into store for the winter, but this explanation left me puzzled. In the end my curiosity was too strong for me and after we had walked a long way I tried to ask her about it again, to which I was quickly given an angry response in a very broad dialect totally beyond my understanding, but her tone was definitely one of annoyance. I concluded that, without any doubt, I must improve my knowledge of the dialect. Finally we reached the felled oak tree and the meal was eaten. The donkey was laden once more and I began my next journey and so it went on throughout that day and all of the next day. During those journeys, going on foot and riding back, I had the chance to get to know my travelling companion better I found out that he belonged to one of the men who were helping us who had brought him along on the day we felled the oak so that he would be available to transport the wood. I learned that his owner was very careful about feeding him and giving him drinks, protecting him from the cold or from excessive heat, shutting him in his stable, which he kept clean, looking after his hooves and his harness; he also took care of his health and his reproduction. I discovered that it was impossible to make the donkey go straight up a really step rise; despite my insistent shouts, use of the “capezza” (the halter) or a stick, he would categorically refuse. He obstinately wished to proceed only in a zigzag fashion taking wide turns; this was the only method that he believed to be opportune for resolving the problem; he was convinced that these difficulties must be approached gradually; practically speaking, he used to break down a problem that otherwise would have been too hard to resolve, into so many easy little problems; his method was efficient and if left to do it his way, he would calmly overcome every steep uphill challenge, reducing the work and avoiding the dangers. Today, memory of this little experience, brings to my mind an application of Cartesian’s method, discovered in 1600; I doubt whether the donkey had studied it to solve his own problems, but I cannot exclude that the illustrious scientist may have seen a donkey walking up a steep slope before he made his discovery. I also had the chance to see the donkey sit down when his load was too heavy; today this example also seems to me to be a form of strike, a protest; I am certain that the donkey did not do it for political reasons; I cannot exclude, however, that whoever invented strikes might not first have seen a donkey protesting in such an effective way. Another thing I noted on those journeys was that if we exaggerated things, even donkeys, patient par excellence, will lose their tempers; when they lose it they begin to run in any direction of their choice, they prick one long ear up and the other down and they bray really loudly; as if to say really forcefully “enough, don’t try it on any more, you’ve broken my …..” |

||

|

|

|

| Working donkeys | carrying firewood | vegetable seller |

| He was a patient worker but he had his own points

of view and his own needs about which he would not reach any

compromise with the man for whom he worked; firstly he demanded

respect; sometimes it seemed to me that he would look me over from

head to toe, in the same disdainful way that in certain cases one

looks at people who are ignorant of many things. I learned that when exasperated he would kick out with both his back legs at the same time which in one fell blow could kill a man; his iron-shod hooves, his strength and his determination are sufficient to explain this. I also learned that that all these characteristics which I had discovered about him are common to all the donkeys in the world and our peasants were well acquainted with this fact. During the long years of my working life, I have met numerous “managers of company human resources”: many of whom treated the men working under them with less knowledge, consideration, respect and care than our peasants used towards their own donkeys. On the return journeys, astride that presumptuous collaborator, who made me clearly understand that he did not need to be guided, I was totally absorbed by everything which slowly flowed past me: the many irregularly shaped plots of land surrounded by blackberry bushes and stone boundaries which stretched as far as the slopes of Monte San Giuliano; the small houses made of white stones, isolated in the fields, the tortuous muddy pathways just wide enough to let the carts pulled by oxen pass through, the occasional peasant who, like a dot lost amongst those fields, sweated to make fruitful his small piece of land which he called: “L ncot”[12]; here and there were several small groups of elm trees; to the right a series of hills and passes sloping down until they were lost to sight. Here and there you could see the white stripe (the so-called new road) that joined the districts and the small stone-built villages perched on spurs of white rock; the green of small woods and lands laboriously tilled by hand but kept like gardens; sheep and an occasional cow at pasture; the rustling of birds flying away; pure uncontaminated air. To the left, in the distance, the pale blue Maiella, as high as the sky, seemed to watch over everything, it kept quiet and stood there up above, impassive; it made you think that there are greater things; with memories of all that I had seen, it seemed as if it were reminding the men, that their passions, their hopes, their illusions, their sweat and their worries, were only short-lived things. Between one journey and another, I saw the men transforming that green mountain which they had chopped down, making it fall onto the plain, into ordered piles of firewood, measured in “canne” (the “canna” of wood was an old unit of measure consisting of a stack of wood about two metres in length, one metre high and one metre wide, thus about two cubic metres; in brief, instead of citing all these dimensions, they just said a “canna” and everyone knew what it meant). The lower part of the oak tree, straight and with few “knots” had been converted into large planks by sawing the trunk itself in vertical sections; this patient work had been carried out using the long two-handled saw with two handles, one at each end. These planks were destined for a different use than the fire; they formed the prime material for the carpenter who created many diverse instruments and equipment. With a cart pulled by oxen, the men had provided firewood for our house in Torricella which was situated a little above the Church of San Giacomo with the off-key bell. At the end of those days of work we had provided firewood to our “Massarì” which was situated in the “Casetta”[13] hamlet and also the house in Torricella; between two nearby trees we had piled up an enormous quantity of twigs, we had planks to fix various problems; our family had procured all that was needed to defend ourselves from the cold. The place where the felled oak had grown was cleaned and at the centre a young oak tree was transplanted with the plan of chopping it down for the same reasons but in thirty years time. At the same time, in other parts of the world, other “evolved men”, in order to carry out physical activities and to take a walk amongst the greenery, had tried in a thousand different ways to make a ball go into a hole and now they were discussing which of them had been the best at doing it. The capacity to play this game filled them with such pride, to the point that they believed they were able to tell everyone else how to live, especially our peasants. Frascati (Rome), end of October 2005 Giosia Aspromonte P.S.

|

|||

|

English translation courtesy of

Dr. Marion Apley Porreca

|